A good month for midges.

Opening my diary to check what I had been up to during September I found

several pages dotted with dead midges no doubt ‘collected’ during an outing to

Rothiemurchus to check out a brilliant population of sedges found by plant expert

Andy a few days earlier. The visit was

made to try and find a new location for the smut fungus growing on heads of

bladder sedge (Carex vesicaria), found only once before by the River Spey near

Kincraig. There were lots of the fungus

on the heads of the more abundant bottle sedge (Carex rostrata) but, despite

lots of false

|

| Skullcap sawfly (Athalia scutellariae) |

alarms, I failed to find anything on the bladder sedge. The wee lochan with the sedges also had a

good population of skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata), a rare plant in these

parts, but even rarer was a caterpillar-like larva that Andy had found,

munching huge holes in many of the plants leaves. The number of larvae suggested a species of

sawfly (just think of sawfly larvae defoliating your gooseberry bushes) and

Andy identified the species as Athalia scutellariae, the skullcap sawfly. This strikingly patterned larva had only been

recorded previously from two locations in Scotland and just once from Highland

in 2014, so one to look out for if encountering its food plant in the

future. The same day our Queen also

broke a record having been on the throne for 63 years and seven months, almost

the whole of my life – amazing.

The ongoing search for Anthracoidea fungus on sedge heads,

particularly on sedges with few records or no records at all in the UK

continued to take me down new paths of discovery. Re-checking a big population of mud sedge

(Carex limosa) near Loch Mallachie took me across Tulloch Moor where I

|

| Greenwich balloon |

found a

deflated balloon (a regular event) complete with coloured ribbon. At the end of

this ribbon was a message asking the finder to email details of the

location. This I did and the thank you

reply informed me that the balloon had been released in Greenwich, London, some

550 miles away. An amazing distance but

I did ask the Tarmac organisers whether adding to the number of balloons now

littering the countryside was a good idea.

I still await a reply. Another

outing saw me heading to a

|

| Club sedge (Carex buxbaumii) |

loch west of Inverness to see a sedge I’d never seen

before – club sedge (Carex buxbaumii).

The initial test would be to find and identify the sedge and if found,

spend a bit of time checking the fruiting heads. A few plants were added to the notebook as I

descended through boggy ground towards the loch including the insectivorous

plants great and round-leaved sundew, plants that would have an unexpected link

to another find later in the day. I

needn’t have worried about identifying the club sedge: quite tall, with an

unusually coloured (green/yellow) flower-head, and quite abundant in a few

locations with five distinct population along the loch shore. In Scotland there are just a few

|

| Red-legged shieldbug (Pentatoma rufipes) |

locations

for this sedge so it was quite good to catch up with it at last. Whilst it wasn’t possible to check all the

sedge heads for the fungus, quite a few were looked at and a growing sense of

excitement was extinguished when the sedge with the right fungus turned out to

be carnation sedge, a a sedge regularly found with the fungus. An insect having a swim in the loch was worth

saving as it was one of the shield bugs and once home my photo helped identify

the red-legged shield bug (Pentatoma rufipes) via the British Bugs

website. My wander round the loch turned

up a tiny quantity of mud sedge which I thought might be new to the site but

expert Ian Green had beaten me to it. In

a small loch-side pool I could also see another unusual plant, a member of the

bladderwort family, and just on the off-chance I would be able to identify it,

I took a small piece of stem and leaves and also with a single side stem

complete with ‘the bladders’. Unlike the

sundews seen earlier the bladderwort is an under-water (aquatic) insectivorous

plant, the bladders being the part of the

|

| Bladderwort (thin leaves in water) and sundew (red/green pads) |

plant that captures the prey items. Sadly, no smut fungi were found on the club

sedges, but it had been a good day in an area I seldom visit. Back home I found some information on

bladderwort identification, but this meant microscope work to look at hairs on

the inside of the bladders! Sadly, this

group of plants seldom produce flowers (apart from lesser bladderwort

(Utricularia minor) see Firwood blog September 2009), so the only way is to

carry out the microscope check. In the

back of my head I remembered the name Utricularia australis (Bladderwort) as

being the species recorded in the past from within Abernethy Forest but that

was possibly before experts got down to the tricky pastime of looking inside

the bladders. So, undaunted, I sliced

one of the bladders open to see what I could see. Inside the hairs grow out from the bladder

wall and it is the shape of these hairs that leads to the plants ID. And sure enough, I was amazed to find a

beautiful patterning comprising the hairs.

|

| Hairs inside bladder of Utricularia stygia |

Photos were sent off to the BSBI expert and the name Utricularia stygia

(Nordic bladderwort) came back. Were the

plants in Abernethy the same species? There

was only one way to find out by combining an outing to check a few more patches

of mud sedge for smuts. The forest bogs

(wet-woodland officially) in Abernethy are, in places, quite extensive, and

were, over many years, the subject of restoration work, removing planted exotic

conifers, blocking drains, and re-wetting the

|

| Bladderwort and stem with bladders |

sites to allow the natural bog

habitats to become re-established. The

best forest bogs were just too wet to have been drained and planted during the

damaging 1960s and 70s, and it was to a couple of these sites that I made my

outing. Once again no smuts were found

on the mud sedge but all the wetter sections of the bogs had abundant

populations of bladderwort and a few small samples were collected for

checking. During the last collection

whilst lifting up enough of the plant to ensure a line of bladders was attached

a rather large spider appeared and I was able to say hello to what has to be

|

| Raft spider (Dolomedes fimbriatus) and bladderwort leaves to left |

my

favourite spider, the raft spider (Dolomedes fimbriatus), a common spider in

Abernethy in this watery habitat. Just

time for a quick photo as it posed with a brilliant patch of bladderwort as a

back-drop. Back home it was back to the

microscope and it very quickly became apparent that there were ‘things’ inside

the some of the bladders, the first one in the shape of a tick! Amazingly, another bladder with tick was

found in another, later collection from another site – well done bladders. On cutting open the bladder I found it was a

tick and just how tick and underwater bladder came together I’ll never know! More

amazing was the tick was still alive in this and the later collection. The hairs

|

| Tick inside bladder |

|

| Ostracoda inside bladder |

inside were the almost perfect

crosses of U. stygia. The next bladders

checked posed a slightly different problem in that there seemed to be a mix of

perfect crosses and crosses with different arm length but when checked by the

expert they were deemed to be the same.

The third collection once again had something within the bladders which

initially looked like tiny eggs. When

the bladder was opened the ‘eggs’ looked like tiny mussel shells with a very

obvious bright spot at what would be the hinge.

I’m not sure how I searched but out popped the name Ostracoda, an

arthropod of the large, mainly aquatic group Crustacea, such as a crab,

lobster, shrimp, or barnacle, so my mussel description wasn’t too far from

correct. Other searches revealed that

Ostracodas are mostly found in slow flowing or still water where they hover over

and amongst the bottom sediments where they feed

|

| A single Ostracoda |

on any small animal or plant

matter stirred up by their movements. I

have to assume that the bladders catch their prey by being able to suck in and

filter the water around them. Goodness,

we know so little about what is going on around us. Without an Ostracoda expert to hand that is

as far as my ID skills can go. So,

amazingly, the plant was a new species for Vice County 96 (East Inverness-shire

with Nairn), and a new species for Abernethy Forest NNR. I just need to find out if U. australis is

there also and see just what else these amazing plants have been eating.

Early September saw the Osmia inermis bee team back in the

Blair Atholl area to re-visit the two sites where the ceramic saucers were

installed to see if we had tempted any bees to use them as nest sites. Sadly, not one of them had been used but

seeing things like vegetation growth around them, dampness within and the

number occupied by tiny ants, a little more thought will need to go into how to

present them on site when the project enters its second year. With a better summer in 2016 it would also be

sensible to try and spend a little more time on site to see if the bee can be found

visiting flowers. However, the visit did

find a site for the lichen Peltigera leucophlebia and the fungal smuts on star

and glaucous sedge (Carex echinata & flacca) so not all wasted despite the

huge disappointment.

The 5th September saw me set off on the last

plant recording session of the summer for the BSBI survey of under-recorded

areas within the Cairngorms National Park.

This outing took me once again to the Spey Dam area close to Laggan

where two previous outings had already been completed. The mainly natural birch woodland on the

hillside to the south of the loch and dam looked so interesting that this visit

would complete plant surveys in the three major habitat types

|

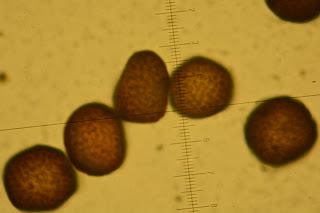

| Carex pallescens and Anthracoidea pseudirregularis smut |

|

| Anthracoidea pseudirregularis spores x1000 oil |

within the tetrad

(2x2 km OS square) I was surveying. Quite

a bit of the birch wood had been enclosed within a deer fence and some of the

lower, tree-less ground had been planted with native broadleaves, and once over

the fence I was in a naturally flushed hillside with runnels and boggy areas

where straight away populations of tawny sedge (Carex hostiana) appeared. A good start.

Wood crane’s-bill was also found as on one of the earlier visits and a

second interesting sedge was found slightly higher up the slope, pale sedge (Carex

pallescens). Due to the dampness of the

site fifteen species of sedge were recorded during the visit with the pale

sedge turning out to be the star of the day right at the end of the day. An ancient goat willow produced what I

thought would be the highlight of the day with lichens Pannaria conoplea and Lobaria

pulmonaria on its trunk but the next patch of pale sedge had black balls of

fungus on its fruits, an Anthracoidea/sedge combination I had

|

| View from hillside with "wee" car |

never

encountered. Would it be unusual, that

would only be determined once back home.

At this stage I was quite a way up the hillside and well into the area

of natural birch woodland with brilliant views back down to Spey Dam and loch

and the tiny green dot which was my wee car!

Back home and the first thing I did was type into Google “Anthacoidea

fungus on Carex pallescens in UK” and the list of options took me to the FRDBI

database where I found there was just one record for a fungus with the unpronounceable

name of Anthracoidea pseudirregularis, found by the late P. W. James on the

island of Mull in 1966. Famous footsteps

to follow indeed.

Ongoing survey work at a site locally threatened with 1500

houses by local volunteer recorders turned up some good records. A phone call to say that something

odd/unusual had been found on the leaves of a small patch of bearberry (Arctostaphylos

uva-ursi) had me visiting the site to confirm that the rare Exobasidium

sydowianum fungus was present. On the

way into the site a few small bees flying around on the sandy track-side

stopped me in my tracks and, with camera at the ready, several were

photographed and videoed so the species could be confirmed. A large colony of Colletes

|

| Colletes succinctus mining bee |

|

| Mellinus arvensis digger wasp |

succinctus (a small

mining bee) had been found and as the bees were watched going about their

business, another small but longer, brighter flying insect was also seen

visiting its breeding holes, the digger wasp Mellinus arvensis. The false morel parasite fungus Cordyceps

ophioglossoides was also growing from the bank as was a group of three Sarcodon

imbricatus, the scaly hedgehog tooth fungus.

About the same time an email arrived detailing a find of a variety of

one of our common clubmosses which looked unusual enough to want to go and try

and find it. The regular variety is fir clubmoss

(Huperzia selago), but a little higher up on our hill/mountain sides is the

subspecies arctica - Arctic fir clubmoss, with records currently (26, 14 of

which are recent finds by local expert Andy) from the Cairngorms area and the

Western Isles. My first thought was to

visit the path taking walkers out to the Chalamain Gap, so with an afternoon free,

I headed off up the Cairngorm road parking near the Sugarbowl car park. The path towards Chalamain Gap drops from the

road to the Allt Druidh and then the climb up the other side takes you past the

reindeer enclosure before levelling out with great

|

| Huperzia selago s.sp arctica |

views of the Northern

Corries. At this point the path reaches

550 to 600m in altitude, about the right elevation to look for the

clubmoss. The first find was a small

group of fir clubmoss plants but with a shape tending towards subspecies arctica,

so hopes were high for the real thing.

All around the deer grass was turning to its orange/brown autumn colour

and there were good patches of bearberry on the bare gravels. The next small population of clubmoss looked

like the plant I was looking for with single plant stems and each with distinct

double whorls of larger leaves spaced up the stem. Right at the top were the double whorls of

this years growth with slightly larger and darker growths called ‘gemmifers’

projecting. These fall off and

presumably allow the plant to vegetatively regenerate itself. Hopefully, the passing group of walkers

didn’t think they had found a body as I lay photographing the plant as they

walked past!

The 24th saw us up bright and early as we drove

over to daughter Ruth’s to pick her up en-route to Eden Court in Inverness for

her BA Graduation Ceremony the culmination of four years of study. I think there were around 500 students packed

into the theatre with at least the same number again of supporting partners,

parents and family members. Resplendent

in their graduation gowns Ruth and her fellow course students made their way

down towards the stage where, one by one they climbed

the steps, walked across

the stage to receive their certificates and posing for a quick official photo

before returning to their seats. A brief

thumbs up from her course tutor as she crossed the stage was in recognition of

not just completing the many assignments but of encouraging her to keep going

whilst coping with the many demands of raising a young family, giving birth to

Harry and moving house four times! Three

weeks later she also successful in getting a place on another three year course

at Elgin College. Help!

The following day saw the culmination of several days of

preparation for the felling of a huge Norway spruce in one of our neighbours

gardens by local tree surgeon Alban and his team. On the way back from collecting the daily

paper Alban gave me the nod that the tree top would be ready for

removal within

the hour so I nipped home to get camera and tripod to capture the event. The top would come off first and gradually

through the day the height of the main stem would be reduced until the main

trunk was of a manageable height to be felled in one go. This fast growing tree was about 1.5m diameter

near its base, way outside the size of anything I had ever tackled in my tree

felling days. When I got back with my

camera Jamie was up at the top of the tree taking off the last few smaller

branches before fixing himself in position to fell the top eight metre section

of the tree with his chainsaw. The

felling notch was made on the felling side of the tree. Jamie then started the

most critical part of

the felling, bringing the saw into the tree from the other side aiming for just

above the top of the felling notch so that a ‘hinge’ would be left to control

the speed and direction of the felling.

With the two cuts complete Jamie then switched off his powersaw using

his strength to lever over the top of the tree, pushing upwards on one of the

branches left on for that purpose. At

first nothing happened, but as Jamie got a rocking motion going, the top of the

tree started to topple over in exactly the right direction as planned. Success, and just before the rain started to

fall. By the end of the day the whole

trunk was on the ground, some of which would be planked into useable sections

rather than just cutting up for firewood.

With fungus expert Liz now no longer resident on Deeside I

made a trip over the tops mid-month to check one of only two known sites for

the tooth fungus Bankera violascens and if present, to undertake the annual

count of fruiting bodies. As I reached

the A93 Deeside road I stopped off to check a notable stand of Sots pines

between the road and the River Dee for other fungi. On the opposite side of the River Dee was the

Woods of Garmaddie, part of the Royal Balmoral Estate. The huge floods that occurred on the Dee in

2014 seemed to have left their mark and only a few of the previously recorded

fungi were found. No doubt, recovery

might take a few years. As I searched a

|

| Cudonia circinans |

call I thought was familiar to me was coming from the river but search as much

as I did, the elusive ‘kingfisher’ wasn’t found. At one stage it sounded like it was just

below me on the side of the river, but still I couldn’t see it. A few Hydnellum ferruginium tooth fungi were

found along with the wrinkled club (Clavulina rugose) and as I started to list

some of the plants present the ‘kingfisher’

|

| Clavulina rugosa |

call started again and once again

quite close to me. Time to sit down and

blend in and await a bit of movement to see my bird. A movement on the opposite side of the river

caught my eye and through my binocs I was able to make out an adult otter

making its way along the bank, occasionally calling. The penny then dropped, my mystery calls

weren’t coming from a bird at all, but from a young otter separated from

probably its mother, by the width of the river!

Time to move on, and after a short drive and uphill walk, I arrived at

the Bankera site to find, as at the only other currently known site for the

fungus, there were fewer fruiting bodies than last year with none at all on one

side of the

|

| Lesser twayblade |

forest track and just 20 on the other. On the damp track side were lots of leaves of

lesser twayblade, with just a few flowering spikes but in the conifer needle

debris a small buff-coloured fungus had me thinking about something growing in

a spruce wood near home, Cudonia circinans, and sure enough when checked at

home this is what it turned out to be. As

I drove back over the tops (Deeside – Lecht – Tomintoul) I had one other

species in my mind to look for, brittle bladder-fern (Cystopteris fragilis), in

an old lime quarry. The quarry had, in

the past, produced several good lichen records, so worth a quick stop. In Strathspey Andy had been taking a small

sample of this fern home to check the spores because the very similar Dickie’s

bladder-fern (Cystopteris dickieana) had turned up in a

|

| Brittle bladder-fern sori with spores top right x40 |

few locations. The lichen Solorina saccata was still present

on some of the rock ledges but the quarry didn’t look quite right for the fern,

but, surprisingly it turned up on the next set of rock ledges. It isn’t possible to check the spores on site

so a small sample has to be taken home, so I checked the back of the fern to

ensure there were sori present (these incurved structures hold the spores and

are ‘spring loaded’ to eject the spores when mature) and to my very pleasant

surprise I found the under-side covered in orange spots indicating a rust

fungus was present. A brilliant article

on “Rust fungi on ferns” by Paul Smith in Field Mycology earlier this year

alerted me to these rusts and despite lots of searching, I had only found the

one on common polypody (Polypodium spp.) previously, so to me

|

| Brittle bladder-fern and rust Hyalopsora polypodii |

this was a ‘real’

find meaning two species for the price of one from the fern frond collected. Back home the fern turned out to be brittle

bladder-fern and the rust, later confirmed by Paul, was identified as

Hyalopsora polypodii, with just 40 previous records in the UK. I couldn’t resist popping into the other

limestone quarry on the edge of Tomintoul as I drove towards home where, once

again the species turned out to be brittle bladder-fern but the bonus here was

finding a tiny population of holly fern (Polystichum lonchitis) in amongst the

rocks, a new location despite probably lots of previous visits by

botanists. As I drove through

Nethybridge on the way home I also noticed another

|

| Shaggy inkcap or lawyers wig |

spectacular fungus growing

in Ross and Ros’s garden, lawyers wig or, more appropriately, shaggy inkcap (Coprinus

comatus). The group comprised three

fruiting bodies, two young ones plus an older one mostly fully intact but with

the cap on one side beginning to liquefy into drips or much more descriptive

deliquesce, as the fungus went about dispersing its spores. Somewhere along the way some animal dung must

have found its way onto their lawn because the generic name Coprinus means

‘living on dung’.

As we said cheerio to Sue and Clifford our chalet guests we

headed down the road to Lancashire to spend a few days with Janet’s mum. Ribchester Arms, Bashall Barn and the Calf’s

Head provided wonderful lunch-time outings augmented by excellent weather. The routes to and from the lunch-stops were

all decided by local knowledge gained by Janet’s 95 years young mum and as we

followed the wee lanes the changing colours of autumn were becoming attractively

obvious. “Turn left and we can go over

Longridge Fell” or “That wee lane is an old Roman Road”, every outing was very

|

| Ribchester Arms for lunch |

informative and expertly guided. Mid-way

through our visit we had planned a day’s shopping(!) mainly to furnish yours

truly with some new shirts and to have a wander round Clitheroe. We gave up on driving on to Skipton and

wandered up and through the old castle before a short walk round the Salthills

Quarry Local Nature Reserve with ferns and limestone in mind. This area was quarried for decades by Ribble

Cement (now Hanson Cement Ribblesdale) and as the quarrying moved to its

current adjacent site the old site started to become home to lots of unusual

plants like lime-loving orchids. My dad

knew the site well and often told me about his finds and those made by the

members of the local natural history group.

We had moved to Scotland by this stage so not a site I had visited at

that time. As the need for industrial

development became pressing much of the old quarry was converted into

industrial units with the small area now comprising the local nature reserve

squeezed in amongst the new developments.

The central section of the reserve is an important area of

|

| Quarry fossils |

calcareous

grassland with just a few of the previous orchids and, during our visit

displaying lots of devil’s-bit scabious and field scabious, betony and agrimony

and on the barer less vegetated area field gentian and the occasional carline

thistle. As we followed the trail back

towards the car I noticed a section of the reserve which looked like it had

been closed off by a locked gate despite there still being numbered information

posts present. This area was mainly the

remains of a quarried rock-face, rich in fossils with a carline thistle rich

flat area which was probably the old quarry floor. Janet was happy to walk back to the car as I

hopped over the gate to see if there was anything unusual along the rock-face

but nothing was found and it was only as I was walking back that I spotted

something that got me quite excited – the leaves of one of the wintergreen

plants. I had a feeling that the three

species I knew about, common, intermediate and round-leaved were all quite rare

or under

|

| Pyrola rotundifolia |

recorded in this part of Lancashire and it was only as I bent down to

have a closer look that I realised I was looking at the round-leaved version, Pyrola

rotundifolia, a plant I had only seen once before over on the NTS Mar Lodge

Estate (see August blog 2011). There

were just five flower-spikes with some flowers well past their best, the ones

still present though all displayed the distinctive down-bending style popping

out from the white petals. I was aware

that there were several populations of this plant in the dunes south of

Southport but wasn’t too sure about whether it had been found in this limestone

area near Clitheroe. Brother John’s

computer provided the answer later in the day – there were no records on either

NBN or the BSBI database. An old school

friend who I mentioned the find to once home did vaguely remember one Rex

Taylor (my dad!) showing him a wintergreen plant in the Salthill area in the

distant past. Wouldn’t that be a great

link to make, particularly as there are a couple of other unusual plant records

on the BSBI Db from the mid-1980s from that area! All too quickly we were heading back up the

M6, M74 in time for our next chalet guest arriving on the Saturday.

That’s it for another month, enjoy the read

Stewart and Janet

British Bugs

Bladderworts

Field Mycology Volume 16(2) April 2015

Rust fungi on ferns – Paul Smith, currently available at

Fungal Records Database of Britain and Ireland (FRDBI)

Salthills Quarry Local Nature Reserve

Ribble Cement/Hanson Cement Ribblesdale (to see scale click

on Downloads top right-hand)

BSBI – Botanical Society of the British Isles

Firwood Cottage blog September 2009

Firwood Cottage blog August 2011

NBN

Highland Biological Recording Group

and how to join HBRG

http://www.hbrg.org.uk/MainPages/joinHBRG.htm

|

| Down at last! |

|

| The great diving beetle (Dytiscus marginalis) Firwood garden |

|

| Spot the green lestes damselflies |

Photos © Stewart Taylor