Indoor work for the early part of the month was completing

data entries for plants recorded during the BSBI/Cairngorms National Park (CNP)

survey covering areas of the Park with few plant records. My commitment covered 5 tetrads (2 x 2km

squares). The enjoyable bit was

wandering and recording, the slightly more tedious bit was entering the

records, but with many happy memories along the way. My five tetrads produced a total of just over

4200 records (records not plant species) with amazing habitats around Spey Dam

producing the most (1400). Overall, this

year’s survey has, so far, produced 27,000 records of 777 species, 152 of which

are on the CNP Rare Plant Register so a brilliant effort by all involved and excellently

organised by BSBI Vice County Recorder Andy Amphlett. Highlights were finding good populations of a

couple of scarce sedges locally, Carex hostiana and Carex pallescens (tawny and

pale sedge) and their Anthracoidea fungi, and getting fixed in my mind that

“molly has hairy knees” when trying to remember which is which of the two

|

| 'Molly has hairy knees' |

Holcus grasses regularly encountered.

Once you get your eye in the difference between these two ‘soft’ grasses

is reasonably obvious but if in doubt look down the plant and Yorkshire fog (Holcus

lanatus) is generally softly hairy. Creeping

soft-grass (Holcus mollis) on the other hand is ‘glabrous’ (no hairs) apart

from ‘white beards at the nodes’, the swollen joints along the grasses stem. Hence the schoolboy mnemonic to distinguish

it from Yorkshire fog, ‘molly has hairy knees’!

After a morning of data entry I went for a walk in one of

the local aspen stands following up a request from Brian C to check for a

rarely recorded parasite of the lichen Physconia distorta, a species I occasionally

see on trunks of older aspen trees.

However, there were too many other distractions, the first one being a

large, orange fungus growing in grassy vegetation amongst the aspens. Long ago, when fungus expert Peter Orton used

to make his annual recording visit to Abernethy Forest, these

|

| Leccinum aurantiacum |

same aspens were

visited to try and find ‘a large orange boletus’ which Peter had been involved

in describing for the first time, as a species new to science. In this same woodland there could always be

the chance of finding the commoner orange birch bolete (Leccinum versipelle)

but, having been caught out with this one once before when found growing under

aspens, (very black scales on the stem of the fungus), I was fairly certain

that the colours on the ‘stipe’ (stem) this time were pointing to something

different. The stipe however, had been

quite badly attacked by slugs, so not quite as obvious as it should have been. This group of fungi have pores under the cap

rather than gills so to help with identification, a small section of the caps

was removed to take home to check for spores.

|

| Sclerophora peronella pinheads |

All the time I was looking at and photographing the fungus several small

flies were landing on it and, I assume, laying eggs in the cap, the fungus

providing a food supply for their larvae once the eggs hatched. If you want to see how many wee larvae live

and grow within a large Boletus fungus, try cutting one open to view the

inside. Having once collected several

ceps/penny buns (Boletus edulis) and popped them into a pan to make mushroom

soup, I was put off ever doing this again by the sheer number of larvae that

came floating to the top of the pan! I

digress. I got back to checking aspens,

briefly, and found a small population of the pinhead lichen Sclerophora

peronella, one of the species ‘missing’ from this particular aspen wood despite

visits by experts and checks of hundreds of aspens

|

| Stump puffball (Lycoperdon pyriforme) spewing spores |

|

| Stump puffball (Lycoperdon pyriforme) |

by myself, many with typical

sections of canker decays, the right habitat for the lichen. A large group of puffballs were the next

distraction, growing from the base of a fallen aspen, so more photos

particularly trying to capture one, of the spores being spewed out. Once home this turned out to be,

appropriately, the stump puffball (Lycoperdon pyriforme), confirmed by checking

the abundant supply of spores. The

distractions continued and around the base of a standing aspen I could see a

large population of inkcaps, not as big and bold as the lawyers wig in the last

blog, but none the less

|

| Coprinopsis atramentaria |

impressive as some of the caps had reached the

deliquescing (inky spore release stage).

There was decay in the aspen base and the common inkcap (Coprinopsis

atramentaria) was popping up in quantity from its typical deadwood

habitat. The big orange fungus turned

out to be not the very rare aspen fungus Leccinum albostipitatum, but its

look-alike Leccinum aurantiacum, confirmed with a little help from expert Liz.

Way back in April, as I was undertaking the aspen ground truthing

work, I came across a group of very big poplars close to the A9 whose catkins

didn’t look right for the tree often just listed as Balsam poplar a species

often found in the Firwood blogs. The

twigs were also covered with the tiny pinhead lichen Phaeocalicium populneum so

I was keen to correctly identify the tree in case it was a

|

| Phaeocalicium populneum pinhead |

new host. At the time there were just catkins but none

of the all-important leaves and little of the strong Balsam scent, so, on the

way back from daughter Ruth’s I pulled off the A9 and wandered over to collect

a twig with a few leaves. Little did I

know what I was starting! I was

suspicious back in April that I was dealing with a hybrid black poplar (Populus

x canadensis) but on checking the leaves in front of me I wasn’t too sure. Hybrid black poplar leaves are green on both

sides, lack any hairs and the leaf stem (petiole) is flat in section. It was obviously not that species and as I

looked at twig and leaves I noticed what looked like a bit of twig attached to

a leaf, which I tried to remove. I

|

| Peppered moth larva (Biston betularia) |

then

realised the ‘twig’ was alive, and was a big caterpillar mimicking brilliantly

the leaf stems and twigs around it, so more photos to help identify the species

once home before carefully removing it and re-attaching to twigs on a low

branch. The caterpillar turned out (with

the help of Mike) to be the larva of the peppered moth (Biston betularia), if

only the poplar had been as easy to identify.

Confused by the contradicting information on the key features of the

leaves of the Balsam poplar group, I passed the leaves on to BSBI expert Andy,

who responded by providing an identification key. However, leaf shape, presence or absence of

hairs again didn’t always seem to correspond with what I had collected and so

started a month of poplar leaf collecting and with Andy’s logic, measuring and

leaf scanning, a picture started to develop for the species of Balsam poplars

we were seeing. All Balsam poplars have

been introduced and have probably proved popular because of their wonderful

display of heavily scented catkins in spring and with much showier leaves than

our native aspen, Populus tremula. They

are also quite large, fast growing trees.

The books list 4 regular

|

| Populus tricocarpa leaf |

|

| Two lengths of hairs on leaf stem of Populus 'Balsam Spire' |

species of Balsam poplars, - Eastern

Balsam-poplar (Populus balsamifera) the one always casually listed as Balsam

poplar when found, Western Balsam-poplar (Populus trichocarpa), and two hybrids

Populus 'Balsam Spire' (a hybrid between P. balsamifera and P. trichocarpa) and

Populus x jackii (a hybrid between P. balsamifera and Populus deltoids a hybrid

black poplar). All the trees have their

origins in America or Canada. As Andy

and I collected leaves he worked at linking the leaf sizes, shapes and stem

(petiole) hairs to those described in the books. The best guidance came from the “New Flora of

the British Isles by Clive Stace” who seemed to have followed exactly the same

method as Andy and gradually leaves from the four species of trees listed

earlier were found. Interestingly, the

tree we casually listed previously has turned out to be the rarest. As the correct species became clearer a big

effort was made to re-visit all the sites where our “Balsam poplar” records had

originated whilst collecting leaves from any new sites along the way. Because I had been visiting these trees to

look for the tiny pinhead lichen I had quite a list of locations and the

conversion from Balsam poplar to the correct species, has, so far produced Western

Balsam-poplar x14 locations, Populus 'Balsam Spire'x5, Populus x jackii x3 and Eastern

Balsam-poplar x2. In addition, leaves I

collected from a site near Aviemore could be yet another species, but much more

information on key

|

| A Balsam Poplar yet to be identified |

tree and leaf features will be needed to complete the

task. At the end of the day the

identifications were made on the shape of the leaves, whether heart-shaped or

triangular and where the leaf was widest and, possibly less problematic,

whether there were any hairs on the petiole and whether all were short, sparse

or of two different lengths. Possibly

the easiest to identify was Populus x jackii with leaf and petiole so hairy the

whole thing felt downy. Andy also became

quite proficient at identifying the trees from branch angles and shape of

crown. Interestingly, the tiny

Phaeocalicium populneum pinhead lichen that started the whole project has been

found on twigs of at least one of the trees of each species identified, and the

tree that started the whole thing is one of the Western Balsam-poplar records. Phew!

There has also been follow up work with the bladder ferns (Cystopteris

species) following the finds mentioned in the last blog. There are two species, the commoner brittle

bladder fern and the rare Dickie’s bladder fern. At one site where I recorded brittle bladder

fern (Cystopteris fragilis) in the past a check by Andy showed the fern to be

the rarer Dickie’s bladder fern (Cystopteris dickieana).

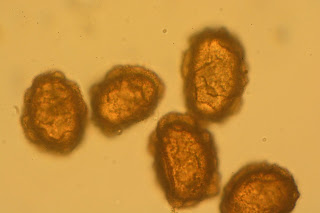

|

| Cystopteris dickieana spores x600 |

|

| Cystopteris dickieana spores x1000 oil |

To confirm the correct species a small

sample, with spores (found on the back of the fronds) had been taken home to

check under the low-powered microscope, and when the spores lacked spines and

showed ‘cracks’ on their surface, Andy knew he had the rarer fern. So, the question raised was whether any of my

other brittle bladder sites had been incorrectly identified, and, during October

six sites were re-visited. The ferns are

mostly found on rock outcrops and, to ensure I knew what the Dickie spores

looked like, I visited the site incorrectly named by me in 2011. With most of the ferns now past their best, mostly

brown and drooping, I tapped a few fronds against a glass slide until I could

see some spores had been dislodged and then secured another glass slide on top

with blutac and packed the whole thing in one of my sealable plastic food boxes

to take home. Dickie’s bladder fern

|

| Cystopteris fragilis spores x600 |

|

| Cystopteris fragilis spores x1000 oil |

is

rare enough to be a protected species and a licence is required to pick or

damage the plant. A Puccinia fungal rust

was also found on the leaves of harebell flowers which has yet to be fully

identified. Back home I put the glass

slide under the microscope and for the first time was able to see Dickie’s

bladder fern spores, spineless and with the black ‘cracks’ on their

surface. One down, six to go. The Bridge of Brown site was confirmed as the

commoner fern but it was the next outing to the Craigmore section of RSPB

Abernethy NNR that produced the first, pleasant surprise. Originally

|

| A typical set of bladder fern fronds (Brittle bladder fern) |

|

| Bladder fern fronds late in the season |

recorded as brittle bladder fern

the small sample of frond taken home (licence not required because species not

known) turned out to be Dickie’s bladder fern, a new species for the reserve. Lesson to be learned, always take a sample

home to check, when fern first found.

The next three were all found to be the commoner version but the last

site, found during the aspen ground truthing survey earlier in the year

produced one small population of brittle but a slightly bigger population of

Dickie’s, possibly, the first time the two have been found growing on the same

crag. The rarer fern was first found by

Dr George Dickie, the same man who first found the tiny fungus on the

twinflower leaves covered in an earlier blog, so nice to link up again.

Whilst checking out the Bridge of Brown site I noticed quite

a lot of heather burning taking place on the adjacent grouse moor, possibly

with a bit more flame and smoke than the keepers would have liked. Dry weather during October has allowed lots of

heather burning with some moors looking a bit ‘over done’. I know this management isn’t very beneficial

to wildlife, destroying as it does many

|

| Muir burn for red grouse |

square kilometres of upland habitat

purely aimed at artificially increasing the number of red grouse available for

shooting, mainly driven grouse shooting.

I’m not against the walked-up form of grouse shooting which supports many

jobs and with benefits to local economies, but to hear that grouse moor

management benefits all sorts of other wildlife including wading birds, just

doesn’t appear true to me when visiting these moors during breeding bird surveys. These ‘benefits’ are supposed to be delivered

because of intensive predator control but again at what costs to wildlife,

particularly our small mammals. The

sheer number of legally set funnel traps (with fen trap inside the cage), is

|

| Funnel trap and fire engine |

immense and, in some places, right in your face as I have been seeing by the

road back from Bridge of Brown. I have considered

for a while stopping to photograph one of two traps set right by this road (the

A939 road between Grantown on Spey and Tomintoul) and on this day, when I saw a

fire engine parked by the same road, I just had to stop to take that

photo. The fires seen earlier had been

out of control, and the local fire brigade had been called in to help out! On other outings I have found a dead dipper

in one of these traps on Crown Estate land near the Lecht, and a thrush in one at

a site near Newtonmore where I also saw the biggest numbers of released

red-legged partridges to date.

Having handed over the reins of the Loch Garten butterfly

transect at the end of last season, I was invited to the recorders’ end of

season gathering at Forest Lodge. With

the meeting planned for early afternoon I drove up early so that I could check

a couple of sites for some of the rarer tooth fungi, one of which (Hydnellum

cumulatum) had failed to appear this year at two of its other known sites. At the first ex-quarry, parting the hanging

vegetation confirmed that Hydnellum gracilipes was still there and looking

quite healthy. At the next quarry it

took a lot more searching to find any trace of H. cumulatum, but eventually a

small amount was found hidden behind hanging vegetation rather than on the top

edge of the old quarry. The search at

this site also produced another seldom seen tiny, orange fan-shaped fungus Stereopsis

vitelline, completing a hat-trick of fungi probably not recorded

|

| Hydnellum gracilipes |

close together

anywhere else in the UK this year. All

seemed to have gone well on the butterfly transect in what was a cool and

testing recording season. The meeting raised

a few queries about recording protocol which were mostly addressed. Alison’s cakes were also very good! Well done the butterfly transect recorders. Whilst looking for the fungi a tiny insect

caught my eye as it wandered across a plant, a miniature form of a

lobster. Having encountered these

amazing wee insects a couple of times before I realised I was looking at a Pseudo-scorpion,

not a scorpion at all but a member of the arachnida, the same family as

spiders. Despite their small size these

animals do look like a small scorpion, but without a sting in the tail. Amazingly, there are 27 known species of

|

| Pseudo-scorpion |

pseudo-scorpions in the UK with 12 of them fairly common. The only way my specimen could be identified

was by going to be checked by an expert, so a name is currently awaited. All this tramping through the deeper

vegetation looking for ‘things’ continues to attract ticks many of which attach

themselves to my body with about ten found on one particularly bad day. Not sure why, but as autumn approaches we

seem to get many more of the bigger, brown variety of this not very welcome

|

| Tick horror waiting for victim |

wee

beastie, and these take a little more effort to pull out with finger nails kept

just that little bit longer during the tick season, just for this task. Once again, the location of one removal

started to develop the dreaded red ring and another two week course of Doxycycline,

Lyme disease tablets had to be undertaken.

I should keep a count of the number of ticks removed in a season just to

shock myself!

The visits to rock outcrops to check for bladder ferns also

produced other interesting sights. At several

locations beech ferns (Phegopteris connectilis) have also been present, a

little past their bright-green summer best as they change to a very subtle

shade of very pale green to almost white.

This fern is easily identified by the way the bottom two pair of

‘leaves’ (pinnae) bend down and

|

| Pale leaves of beech fern (Phegopteris connectilis) |

|

| Frond and sori of lemon-scented fern (Oreopteris limbosperma) |

forward a little from the other leaves. Another common fern in the damper rock

outcrop locations is lemon-scented fern (Oreopteris limbosperma). Initially this fern looks like many of the

other large ferns like male fern but turning it over to check the underside of

the leaves helps to identify it. You

will find all the spore-bearing sori run along the outside edge of the

secondary ‘leaves’ (pinnules) making identification fairly easy. At another rock outcrop it was nice to be

re-acquainted with the orange fungus growing round the stems of a group of

grasses. This is the Choke fungus (Epichloë

typhina) and one thing I noticed for the first time was that the grass stems

with the fungus didn’t have any flower-heads.

On checking sites on the internet I found that the common name is

explaining

|

| Choke fungus |

what the fungus does to the grass – it chokes it, leading to the

loss of seed production, hence no flower-heads.

The fungus also makes the grass less susceptible to grazing by

herbivores, yet another mix of symbiotic relationships. There is also a fly involved in ensuring the

fungus is spread around successfully. I

also found out that the fungus might not be E. typhina, as six species of Epichloë

have been recorded in Britain. More

specimen collections needed in the future!

One of the Choke sites was found whilst checking the amazingly

productive green shield-moss site found last year, where

|

| Pink feet passing over |

around 150 capsules

were found. This doesn’t appear to be a

good year for capsule production with just 10-20 capsules present this

year. However, about 50 new capsules

were found on a Norway spruce root-plate just a few metres away. Whilst out and about there were lots of

mainly pink-footed geese passing over and towards the end of the month the

first redwings were arriving.

RSPB/Community Ranger Alison also had an amazing count, 63 whooper swans

roosting on Loch Garten, the highest count to date.

Whilst looking after grandsons Finlay and Archie I decided

to take them to see the Glenmore reindeer, not at the reindeer centre but in

the enclosure by the road up to Cairngorm.

Having passed the same enclosure several times this year I had always

seen the reindeer in the area where they are

|

| There they are |

fed and where visitors are taken

to see them. No problem then. We parked off the Cairngorm road and spent

the first half an hour messing about climbing on the branches of an ancient but

leaning Scots pine, well Finlay and Archie did!

After descending down to the Allt Mor burn we climbed out on the other

side and eventually arrived at the enclosure with not a reindeer to be seen,

well not within easy viewing distance.

However, looking quite a way up the path a couple of reindeer were

grazing right by the path and close by there were more inside the enclosure

fence. Phew! So, with

|

| Success! |

the promise of chocolate biscuits if

we carried on up the path to where the animals were, on we walked. Because these reindeer are used to meeting

visitors the ones outside the fence just carried on grazing as we approached,

and the big snorting male inside the fence seemed determine to try and see off

the couple of males on the outside of the fence. All good fun and as we sat to munch our

biscuits I was a little surprised that the reindeer didn’t wander over to see

if we had some for them.

Whole body scans were also something new during the month

and the nurse wasn’t joking when she said for one of the scans it would be like

going into a building site! But more

about these in future blogs. Also, on

the 24th the first snows appeared on the tops but the month ended

with temperatures in the mid-teens.

Enjoy the read

Stewart and Janet

Grass structures

Dickie’s bladder fern Firwood blog October 2007

Dr George Dickie twinflower and bladder fern Firwood blog

May 2013

Mark Avery’s blog with more information about grouse moors

and hen harriers

Introduction to parts of a fern

Buglife link to pseudo-scorpions

Fungal Records Database of Britain and Ireland (FRDBI)

BSBI – Botanical Society of the British Isles

NBN

Highland Biological Recording Group

and how to join HBRG

|

| Heavy rain at Loch Mallachie |

|

| To complete a rainy end - rainbow over Dorback Estate |

Photos © Stewart Taylor